APOD: 2025 April 28 – Gum 37 and the Southern Tadpoles

This cosmic skyscape

features glowing gas and dark dust clouds alongside the young stars of

NGC 3572.

A beautiful emission nebula and star cluster, it sails

far southern skies within the

nautical constellation Carina.

Stars from NGC 3572 are toward top center

in the telescopic frame that would measure about 100

light-years

across at the cluster's estimated distance of 9,000 light-years.

The visible interstellar gas and dust, shown in

colors of the

Hubble palette,

is part of the star cluster's natal

molecular cloud,

itself cataloged as

Gum 37.

Dense streamers of material within the nebula, eroded by stellar winds and radiation, clearly trail away from the energetic young stars.

They are likely sites of ongoing star formation with shapes reminiscent of the

Tadpoles of IC 410 -- better known to northern skygazers.

In the coming tens to hundreds of millions of years, gas and stars in the cluster will be dispersed though, by

gravitational tides and by violent

supernova explosions that end the short lives of the massive cluster stars.

APOD: 2025 April 28 – Gum 37 and the Southern Tadpoles

This cosmic skyscape

features glowing gas and dark dust clouds alongside the young stars of

NGC 3572.

A beautiful emission nebula and star cluster, it sails

far southern skies within the

nautical constellation Carina.

Stars from NGC 3572 are toward top center

in the telescopic frame that would measure about 100

light-years

across at the cluster's estimated distance of 9,000 light-years.

The visible interstellar gas and dust, shown in

colors of the

Hubble palette,

is part of the star cluster's natal

molecular cloud,

itself cataloged as

Gum 37.

Dense streamers of material within the nebula, eroded by stellar winds and radiation, clearly trail away from the energetic young stars.

They are likely sites of ongoing star formation with shapes reminiscent of the

Tadpoles of IC 410 -- better known to northern skygazers.

In the coming tens to hundreds of millions of years, gas and stars in the cluster will be dispersed though, by

gravitational tides and by violent

supernova explosions that end the short lives of the massive cluster stars.

APOD: 2025 April 28 – Gum 37 and the Southern Tadpoles

This cosmic skyscape

features glowing gas and dark dust clouds alongside the young stars of

NGC 3572.

A beautiful emission nebula and star cluster, it sails

far southern skies within the

nautical constellation Carina.

Stars from NGC 3572 are toward top center

in the telescopic frame that would measure about 100

light-years

across at the cluster's estimated distance of 9,000 light-years.

The visible interstellar gas and dust, shown in

colors of the

Hubble palette,

is part of the star cluster's natal

molecular cloud,

itself cataloged as

Gum 37.

Dense streamers of material within the nebula, eroded by stellar winds and radiation, clearly trail away from the energetic young stars.

They are likely sites of ongoing star formation with shapes reminiscent of the

Tadpoles of IC 410 -- better known to northern skygazers.

In the coming tens to hundreds of millions of years, gas and stars in the cluster will be dispersed though, by

gravitational tides and by violent

supernova explosions that end the short lives of the massive cluster stars.

APOD: 2025 April 28 – Gum 37 and the Southern Tadpoles

This cosmic skyscape

features glowing gas and dark dust clouds alongside the young stars of

NGC 3572.

A beautiful emission nebula and star cluster, it sails

far southern skies within the

nautical constellation Carina.

Stars from NGC 3572 are toward top center

in the telescopic frame that would measure about 100

light-years

across at the cluster's estimated distance of 9,000 light-years.

The visible interstellar gas and dust, shown in

colors of the

Hubble palette,

is part of the star cluster's natal

molecular cloud,

itself cataloged as

Gum 37.

Dense streamers of material within the nebula, eroded by stellar winds and radiation, clearly trail away from the energetic young stars.

They are likely sites of ongoing star formation with shapes reminiscent of the

Tadpoles of IC 410 -- better known to northern skygazers.

In the coming tens to hundreds of millions of years, gas and stars in the cluster will be dispersed though, by

gravitational tides and by violent

supernova explosions that end the short lives of the massive cluster stars.

Enlarge / Asian woman with protective face mask using smartphone while commuting in the urban bridge in city against crowd of people (credit: d3sign via Getty Images)

On March 28, 2020, as COVID-19 cases began to shut down public life in much of the United States, then-Surgeon General Jerome Adams issued an advisory on Twitter: The general public should not wear masks. “There is scant or conflicting evidence they benefit individual wearers in a meaningful way,” he wrote.

Adams’ advice was in line with messages from other US officials and the World Health Organization. Days later, though, US public health leaders shifted course. Mask-wearing was soon a pandemic-control strategy worldwide, but whether this strategy succeeded is now a matter of heated debate—particularly after a major new analysis, released in January, seemed to conclude that masks remain an unproven strategy for curbing transmission of COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses.

“There’s still no evidence that masks are effective during a pandemic,” the study’s lead author, physician, and epidemiologist Tom Jefferson, recently told an interviewer.

Many public health experts vigorously disagree with that claim, but the study has caught attention, in part, because of its pedigree: It was published by Cochrane, a not-for-profit that aims to bring rigorous scientific evidence more squarely into the practice of medicine. The group’s highly regarded systematic reviews affect clinical practice worldwide. “It’s really our gold standard for evidence-based medicine,” said Jeanne Noble, a physician and associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. One epidemiologist described Cochrane as “the Bible.”

The new review, “Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses,” is an updated version of a paper published in the fall of 2020. It dropped at a time when debates over COVID-19 are still simmering among scientists, politicians, and the broader public.

For some, the Cochrane review provided vindication. “Mask mandates were a bust,” conservative columnist Bret Stephens wrote in The New York Times last week. “Those skeptics who were furiously mocked as cranks and occasionally censored as ‘misinformers’ for opposing mandates were right.”

Meanwhile, masks continue to be recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which describes them as “a critical public health tool.” And this winter, some school districts issued short-term mandates in an effort to curb not just COVID-19, but other respiratory viruses, including influenza and RSV.

The polarized debate conceals a murkier picture. Whether or not masks “work” is a multilayered question—one involving a mix of physics, infectious disease biology, and human behavior. Many scientists and physicians say the Cochrane review’s findings were, in a strict sense, correct: High-quality studies known as randomized controlled trials, or RCTs, don’t typically show much benefit for mask wearers.

But whether that means masks don’t work is a tougher question—one that has revealed sharp divisions among public health researchers.

The principle behind masks is straightforward: If viruses like SAR-CoV-2 or influenza can spread when droplets or larger particles travel from one person’s nose and mouth into another person’s nose and mouth, then putting up a barrier may slow the spread. And there’s certainly evidence that surgical masks can block some relatively large respiratory droplets.

Early in the pandemic, though, some researchers saw evidence that SARS-CoV-2 was spreading via tinier particles, which can linger in the air and better slip around or through surgical and cloth masks. “Sweeping mask recommendations—as many have proposed—will not reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission,” respiratory protection experts Lisa Brosseau and Margaret Sietsema wrote in an April 2020 article for the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

Their colleague Michael Osterholm, a prominent epidemiologist, was more blunt: “Never before in my 45-year career have I seen such a far-reaching public recommendation issued by any governmental agency without a single source of data or information to support it,” he said on a podcast that June. (The Minnesota center receives funding from 3M, which manufactures both surgical masks and respirators.)

In a recent interview with Undark, Brosseau stressed that she thinks cloth and surgical masks have some protective benefit. But she and others, including Osterholm, have urged policymakers to emphasize tight-fitting respirators like N95s, rather than looser-fitting cloth and surgical masks. That's because there’s clear evidence that respirators can effectively ensnare those tiny particles. “A well-fitting, good quality respirator will trap the virus, almost all of it, and will greatly reduce your exposure to it,” said Linsey Marr, an engineering professor at Virginia Tech who studies the airborne transmission of viruses.

When air flows through a respirator, it passes through a dense mesh of fibers. Those tiny particles collide with the fibers and get stuck, thanks to electrostatic forces—the same force that makes hair stick to a balloon.

There is “a huge reduction in the number of particles that get through,” Marr said. (Indeed, the "95" in the N95 rating indicates that a mask, used properly and under the right conditions, is designed to capture roughly 95 percent of airborne particles.)

A popular online physics education channel offers an animated breakdown of how N95 masks work to reduce exposure to airborne particles.

In the laboratory, researchers can actually test out respirator performance. For one paper, published in 2020, scientists placed two mannequin heads in a translucent box. Using a nebulizer and actual SARS-CoV-2 virus, they piped “a mist of virus suspension” through the mouth of one mannequin, mimicking an exhaling person. They used a ventilator to draw air into the other mannequin’s mouth. Finally, they fitted the mannequins with various combinations of masks, respirators, or nothing at all, and tested how much of the virus evaded capture as it journeyed between the mannequins. Cloth and surgical masks did have an effect — but were substantially outperformed by the N95s, which captured most of the viral particles.

Just because an N95 captures particles in the lab, however, doesn’t necessarily mean it will stop an actual person from getting infected out in the world. Part of the issue is that people don’t always wear respirators properly. And, even if the respirator performs well, the viral particles that slip through could be enough to make a person sick anyway. In the mannequin study, even an N95 taped snugly to a mannequin’s face failed to capture all the particles.

One 2020 study using mannequin heads found that cloth and surgical masks did have an effect—but were substantially outperformed by the N95s, which captured most of the viral particles. (credit: American Society for Microbiology)

MacIntyre and her colleagues reported that the people who wore N95s all day were significantly less likely to develop a respiratory illness than everyone else.

Other studies have produced mixed results. Some found that the masks or respirators had a small effect on someone’s odds of getting sick, but not always enough to be considered statistically significant. Others didn’t find any benefit at all when comparing N95s to surgical masks, or even surgical masks to non-masking.

Do those findings apply, though, when millions of people are masking together, in the middle of a pandemic? At this scale, the question of whether or not masks work can be treated as a policy question: Did mask requirements actually reduce the spread of COVID-19? But doing a randomized controlled trial to answer this question is probably impossible, said Jing Huang, a biostatistician at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. It’s not easy to just ask a few dozen randomly selected cities to implement mandates, and a few dozen to avoid mandates, and then track what happens.

And yet, this scenario did happen naturally during the COVID-19 pandemic: Some places put in mask mandates, and others did not. This sort of natural experiment opened up an opportunity for researchers to sift through health data in these different locations and try to suss out patterns—and Huang and her colleagues recently did just that. They matched 351 counties in the United States that had implemented mask mandates with counties that did not have a mandate, but that were otherwise similar in several other respects. This means that, when possible, the COVID rates in a Republican-leaning, suburban county in the South that implemented a mask mandate during moderate COVID-19 spread would be measured against infection rates in another right-leaning, suburban Southern county that did not put a mandate into place at the same time.

Huang's analysis found that mask mandates were associated with substantially dampened COVID-19 spikes, although the benefit waned over time in some counties. The reason behind that waning was unclear, but could perhaps be could be due to fatigue with the mandates, the researchers suggested. Similar studies have often—but not always—found a positive effect.

Whether the masks were responsible for those benefits, though, was hard to pin down, Huang said. It’s possible that other factors—such as other policies implemented alongside mask mandates, or greater social distancing—actually kept COVID-19 rates lower, rather than the masks themselves. “I think it’s very difficult,” Huang said, “to make a causation conclusion.”

The CDC has cited other observational studies to justify its masking recommendation. One 2022 study found that people in California who chose to wear N95s were less likely to catch COVID-19 than people using other kinds of respiratory protection, who were themselves less likely to fall ill than people did not wear a mask at all. But the study was criticized for doing little to control for all the other ways people who wear N95s may behave differently than people who never wear masks. Was it the masks that made the difference? Or was it those other cautionary behaviors that people who tend to wear N95s also engage in that reduced their risk?

Cochrane’s methods were designed precisely to unravel these kinds of vexing medical questions. The organization was launched in 1993, with the mission, as reporter Daniel Kolitz wrote in a feature for Undark, of “gathering and summarizing the strongest available evidence across virtually every field of medicine, with the aim of allowing clinicians to make informed choices about treatment."

Today, Cochrane maintains a network of thousands of affiliated researchers, who produce hundreds of reviews each year while working under the Cochrane banner. Those reviews tend to answer very specific questions: For example, does taking vitamin C reduce “the incidence, the duration or severity of the common cold”? Each team first searches the vast scientific literature, trying to amass an exhaustive list of relevant published and unpublished studies. Then, they select studies that meet Cochrane’s thresholds for rigor, and systematically organize and synthesize the data, aiming to produce a succinct answer to the original question.

Those reviews prioritize randomized controlled trials—things like the experiment with the Beijing health care workers—over other kinds of studies.

Tom Jefferson, who is an instructor in the Department for Continuing Education at the University of Oxford, is the first author on Cochrane's recent masking review. For nearly two decades, he’s been part of a Cochrane team that examines the effects of certain interventions on the spread of respiratory viruses. The team has considered a range of questions: Do respirators help slow the spread of respiratory illnesses? Does handwashing? Does gargling?

Jefferson’s group published its first systematic review of these kinds of questions in 2006. For the most recent, updated review, Jefferson and 11 collaborators synthesized evidence from 78 such RCTs, including 18 studies that specifically examined mask and respirator use. (They also looked at five ongoing studies, including two that look at mask use.) Their conclusion is principally about the absence of evidence: Taken together, they found, those studies simply do not offer evidence that asking people to wear an N95 instead of a surgical mask significantly reduces their odds of getting sick. Similarly, they did not find evidence that wearing surgical masks offered an advantage over wearing nothing at all.

Few of the studies took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, instead looking at infections during cold and flu seasons. And the majority of the studies only looked at whether masks and respirators protect the wearer from getting sick — not whether they reduce the odds that a sick mask-wearer will infect other people.

Some researchers agree that randomized controlled trials don’t currently show clear-cut evidence that masks and respirators reduce the wearer’s odds of getting sick. But, they argue, RCTs may not actually be the best source of evidence for determining whether masks confer protection. “Strictly speaking, they're correct that there's no statistically significant effect,” said Ben Cowling, an epidemiologist at the University of Hong Kong whose research is cited in the Cochrane review. “But when you look at the totality of evidence, I think there's a pretty good indication that masks can protect people when they wear them.”

In particular, Cowling said, mechanistic studies—like those conducted with mannequins—do offer strong evidence that respirators cut down on the passage of viral particles.

Huang, the Penn biostatistician, is among others who argue that, in many RCTs examining mask use, the sample sizes are just too small. Even if masks are effective, that may not show up as a statistically meaningful result. “When the effect is moderate, or small, we really need a large sample size to find a significant difference,” said Huang. Many of these RCTs, she said, simply weren’t large enough to find some potentially meaningful signal.

And even if the effect is modest, during peak periods of a pandemic, small advantages can have a large impact by reducing the number of sick patients seeking hospital care at the same time. “From a public health perspective," said Cowling, "reducing the reproductive number by even 10 percent could be valuable."

For a complex issue like masks, Trish Greenhalgh is among other researchers who suggest that an RCT may be an imperfect tool. “I'm not against RCTs,” said Greenhalgh, a physician and health researcher at the University of Oxford. “But they were never designed to look at complex social interventions."

Greenhalgh is an influential figure in the evidence-based medicine movement—her book How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine and Healthcare is in its sixth edition—but she has at times been critical of what she characterizes as an overreliance on RCTs. Greenhalgh characterized some of her colleagues as, in effect, RCT hardliners—focused on RCTs at the expense of considering other kinds of evidence. In that mindset, she said, “it seems that an RCT, however bad, is better than an observational study, however good."

Cochrane’s own leadership seems to share some of those concerns. In November 2020, when Jefferson’s team published an earlier version of their review, Cochrane published an accompanying editorial, warning policymakers to move cautiously with the results, and not to interpret them as definitive evidence that masks and respirators don’t work. Instead, the group wrote, “there may never be strong evidence regarding the effectiveness of individual behavioral measures.”

Some observers have suggested that such warnings are more about politics than science.

In an interview with the journalist Maryanne Demasi, Jefferson accused Cochrane of slow-walking an earlier version of the review, and of writing the editorial in order “to undermine our work.” (In an email sent to Undark via Harry Dayantis, a Cochrane spokesperson, the editor in chief of the Cochrane Library, Karla Soares-Weiser, said the processing time was standard for such a long review. "We wrote the editorial to help contextualize the review in the hope that it would help to prevent misinterpretations of the findings,” she wrote. “As we've seen from the response to the 2023 update, the risk of misinterpretation is very real!”)

The review is not the first time that Jefferson has found himself challenging prevailing medical opinion. Years ago, he drew attention for arguing that the benefits of influenza vaccines had been overstated. (A 2009 article in The Atlantic described him as “the most vocal—and undoubtedly most vexing—critic of the gospel of flu vaccine,” noting that he had become “something of a pariah” among flu researchers.) He has spent years arguing that the drug oseltamivir, also known as Tamiflu, and another antiviral medication may be less beneficial for influenza patients than drugmakers and public health authorities have claimed. More recently, he and another author on the Cochrane review, Canadian physician and World Health Organization adviser John Conly, have questioned the role of small airborne particles in transmitting SARS-CoV-2.

Jefferson has also done some writing for The Brownstone Institute. Founded by libertarian Jeffrey Tucker, the organization is broadly opposed to public health restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jefferson declined to be interviewed for this article, sharing links to three Substack posts in which he criticizes press coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Most media are as complicit in spreading fear and panic as governments and their psyops people,” he writes in one of the posts, going on to draw an analogy between reporters and Nazi functionaries.

Attempts to arrange interviews with four other authors of the Cochrane review, including Conly, were unsuccessful.

At times, the conversation about masks can verge on larger questions about human nature, and about how research should take into account the messiness of people’s behavior.

At issue is a contentious detail: In many of the RCTs analyzed in the Cochrane review, it’s not clear whether the people who were told to wear masks or respirators actually did so consistently and correctly. In addition, many such studies only ask people to wear respiratory protection for part of the day, meaning even if the mask or respirator works to stop infections when it’s on, the wearer may just get sick at other times. Marr, the Virginia Tech professor, compared this to a study that asks people to wear condoms only half the time they have sex: “What do you think’s going to happen?"

Some people are skeptical that such distinctions really matter, at least when it comes to policymaking. “Your policy has to exist in the real world. That's the thing,” said Shira Doron, a physician and the chief infection control officer at Tufts Medicine. A respirator, used perfectly and continuously, may work to reduce the spread of COVID-19. But if there’s a public health intervention that requires strict adherence, and almost nobody seems willing or able to follow it, is that actually an effective intervention at all? What does it even mean to say that it works?

Noble, the emergency physician, has led the UCSF Hospital emergency department’s COVID-19 response. Perfect masking, she said, is out of reach for many people. In some cases—she brought up elderly patients who struggle to communicate when masked—it can even have harms. And masking policies, she said, don’t always seem to recognize that reality, especially at a stage in the pandemic when vaccines are widely available. Her own work suggests that even fitted respirators, worn by health care workers, can swiftly lose their shape and fit, perhaps undercutting their protective benefits. "It's just harder to fit a human being than it is a mannequin,” she said. “And then we just cannot wear them correctly, for any length of time, because of the discomfort.”

Doron spoke warmly about the Cochrane review, while stressing that it had limits. "This study has concluded, not that masks don't work, but that there is not evidence that masking on a population level decreases the incidence of infection. That's what it proves,” she said. She still thinks a good, well-fitting respirator can help prevent someone from catching COVID-19. “Why do I think that I think that? Because of the totality of evidence from non-RCTs that address that question. But do I know it? No, I do not.”

It can be difficult to determine what all of this evidence—and gaps in evidence—mean for mask mandates. Cowling spoke with Undark via Skype from Hong Kong, where officials continued to enforce a mask mandate until this week, issuing steep fines for people who did not cover up in public spaces, both indoors and outdoors.

Cowling, who heads the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Hong Kong’s School of Public Health, expressed doubts about that kind of policy. He argued that the evidence is clear that widespread masking, deployed during a pandemic surge, may help to flatten the curve and save lives. “That's the exact scenario that public health measures are designed for,” he said. But “that's not the way they've been used in the last years,” he added.

"What's happened in many parts of the world is that measures are brought in and kept in place,” Cowling said, “far longer than they're needed."

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

I'm one of the few that's still masking, due to my wife's illness, and we haven't gotten covid yet. I wear a proper n95 underneath a cloth mask anytime I'm indoors with other humans (other than at home), and I generally avoid large gatherings and going out to eat. I know it's still a matter of time before we get it, even with the masks, but it's all about risk reduction.

Enlarge / Not pictured: the things that are far more dangerous to fortress-dwelling dwarves, like poor site planning, miasma, and a lack of drink.

After a long night of playing Dwarf Fortress, I had a concerned look on my face when I finally went to bed. My wife asked what was wrong. "I think I actually want to keep playing this," I said. I felt a nagging concern for many weeknights to come.

Available tomorrow on Steam and itch.io, the new version of Dwarf Fortress updates the legendary (and legendarily arcane) colony-building roguelike with new pixel-art graphics, music, some (default) keyboard shortcuts, and a beginners' tutorial. The commercial release aims to do two things: make the game somewhat more accessible and provide Tarn and Zach Adams, the brothers who maintained the game as a free download for 20 years, some financial security.

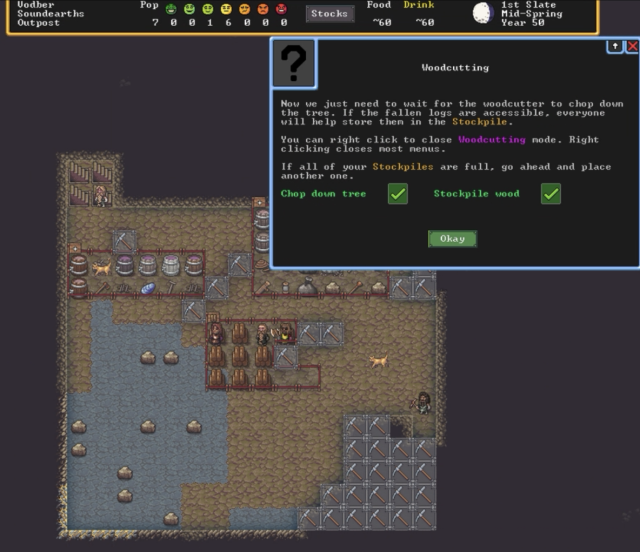

It may look simple, but these tips on how to cut down wood and where to stash it will probably save the average player at least an hour and maybe a couple of failed playthroughs. (credit: Kevin Purdy / Kitfox Games)

I know it has succeeded at its first job, and I suspect it will hit the second mark, too. I approached the game as a head-first review expedition into likely frustrating territory. Now I find myself distracted from writing about it because I keep thinking about my goblin defense and whether the fisherdwarf might be better assigned to gem crafting.

Getting hooked

Nearly 10 years ago, Ars' Casey Johnston spent 10 hours trying to burrow into Dwarf Fortress and came out more confused than before. The ASCII-based "graphics" played a significant role in her confusion, but so did the lack of any real onboarding, or even simple explanations or help menus about how things worked. Even after begrudgingly turning to a beginners' wiki, Johnston found nothing but frustration:

Where’s the command to build a table? Which workshop is the mason's? How do I figure that out? Should I just build another mason’s workshop because that may be faster than trying to find the right menu to identify the mason’s workshop?

In a few hours' time—and similarly avoiding the wiki guide until I'd tried going it alone for my first couple of runs—I got further into Dwarf Fortress' systems than Johnston did with her 10-hour ordeal, and I likely enjoyed it a good deal more. Using the new tutorial modes' initial placement suggestions and following its section-by-section cues, my first run taught me how to dig down, start a stockpile, assign some simple jobs, build a workshop, and—harkening back to Johnston's final frustrations—craft and place beds, bins, and tables, made with "non-economic stone."

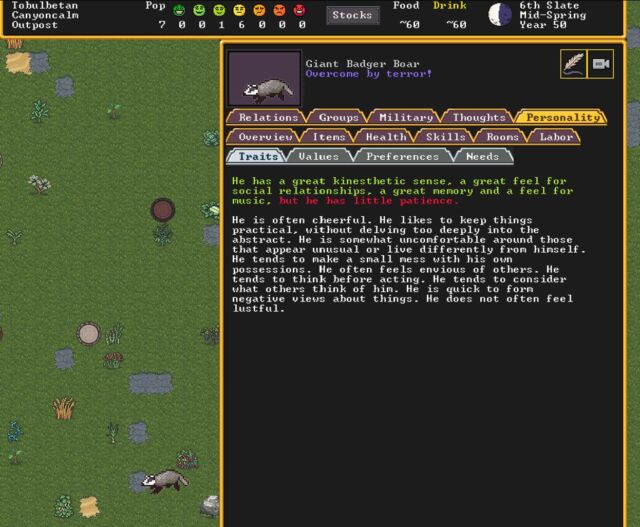

One of the badgers that terrorized an early settlement—and his surprisingly rich inner life. (credit: Kevin Purdy / Kitfox Games)

That's about where the guidance ends, though. The new menus are certainly a lot easier to navigate than the traditional all-text, shortcut-heavy interface (though you can keep using multi-key combinations to craft and assign orders if you like). And the graphics certainly make it a lot easier to notice and address problems. Now, when an angry Giant Badger Boar kills your dogs and maims the one dwarf you have gathering plants outside, the threat actually looks like a badger, not a symbol you'd accidentally type if you held down the Alt key. If you build a barrel, you get something that resembles a barrel, which is no small thing when you're just getting started in this arcane world.

The newly added music also helps soften the experience for newcomers. It's intermittent, unobtrusive, and quite lovely and evocative. It seems designed to stave off the eeriness of too much silent strategizing without overstaying its welcome. I can appreciate a game that graphically evokes the 16-bit era without the audio-cue exhaustion common to the JRPGs and simulations of the time.

-

A magma-adjacent cavern. [credit: Kitfox Games ]

However gentler the aesthetics and guidance for a newcomer, all the game's brutally tough and interlocking systems are intact in this update. These systems crunch together in weird and wild ways, fed by the landscape, your recent and long-ago actions, and random numbers behind the scenes.

My first run ended in starvation and rock-bottom morale ("hissy fits" in common wiki language) because farming, butchering, and other procurements aren't covered in the tutorial. I shut down my second run early after picking a sandy area with an aquifer as a starting zone, thinking it would make glasswork and irrigation easier and being quickly disappointed with this strategy. I was proud on my third run to have started brewing and dispensing drinks (essential to dwarves' contentment), but I dug too close to a nearby river, and I abandoned that soggy fort as yet another lesson learned.

But I'll be back. For me, the commercial release of Dwarf Fortress succeeded at transforming the game from a grim, time-killing in-joke for diehards into a viable, if not graceful, challenge. I will start again, I will keep the badgers and floods at bay, and next time, I might have the privilege of failing to a magma monster, an outbreak of disease, or even a miscarriage of dwarf justice.

They say a week is a long time in politics, but it’s a lifetime on the internet. Like everyone else, we’ve been watching the goings on at Twitter with interest, and more than a dash of concern. Then the layoffs happened. It was time to get a lifeboat ready. After a lot of debate here at Pi Towers, we’ve now spun up our own Mastodon instance. The best thing about it? It’s running on a Raspberry Pi 4 hosted at Mythic Beasts.

It’s running on a Pi in the Sky ☁️.

Last week, Elon Musk walked into Twitter HQ carrying a kitchen sink, and within hours he had laid off half of Twitter’s staff. The lawsuits, then rehiring, started almost immediately afterwards. With the content moderation team cut to the bone, anecdotally at least, folks also started to see an uptick in abuse, spam, and other things. The changes in the way verification is going to work are worrying, and confusing. There are even discussions ongoing about putting the entire site behind a paywall.

That’s a lot of change in a short amount of time. So if you no longer feel like Twitter is a place to be, as some celebrities and academics have already, then you can now also follow us over on Mastodon.

If you haven’t yet joined you can sign up over at Mastodon.

What’s Mastodon? 🐘

Mastodon is yet another social media platform.

That doesn’t tell you a lot, does it? Let’s try that again.

Mastodon is an open-sourced Twitter alternative running as part of something called “the Fediverse.” Unlike platforms like Twitter or Facebook, Mastodon is federated. That means it’s decentralised. There isn’t just one central site where you can go and sign up, like you do for Twitter; instead there are lots of sites all of which talk to each other using a protocol called ActivityPub.

You can sign up to any Mastodon site — which are called instances — and you can follow folks who are on your own, or on any other, instance which is part of the fediverse. Instances all talk to each other, so which instance you’re on doesn’t generally make much of a difference to who you can follow, or who can follow you.

However, your instance is your “local community.” The instance you join could be for you and your friends, or it could be about what you do in your spare time, or for work. For instance, there are communities built around special interest groups like open-source software or cyber security, and geographical ones, like Scotland.

Why did you join Mastodon?

There are two main practical concerns. One is sociological, one is technical.

The changes coming to Twitter look to fundamentally change the way the site feels. The dramatic cuts that the moderation team seems to have taken will open up the platform to spam, scams, and other things that we don’t want to have to deal with on a day-to-day basis. But there are also issues around identity, and I’ve been thinking a lot about identity verification and trust since the announcements.

The announcements around Twitter Blue are concerning not because they give wider access to identity verification; we’d welcome that. Instead they don’t seem to do the opposite. It comes down to what identity itself means: a blue tick next to someone on Twitter no longer means that their identity has been verified by an employee of the company; it means that they can afford $8 a month. That’s not the same thing.

But putting all of that aside, Twitter is going to face technical problems. It probably won’t be a sudden and catastrophic collapse — in my head I have an image of a disk slowly filling up somewhere in Twitter’s data centre, and the site going down hard when it is full — it’s far more likely to be an accumulation of technical debt. Issues will pile up as the backlog of maintenance tasks and fixes that the reduced workforce just can’t get ahead of increases, and eventually, the site will end up as an unstable wreck. That isn’t good for any of us.

How do I join?

There are two ways you can join Mastodon. You can create an account on an existing instance, or you can create your own instance to host your own community and join the fediverse that way.

Because Mastodon is federated, joining an existing instance isn’t quite as simple joining a monolithic service like Twitter. You can sign up to any Mastodon instance to join the fediverse, and you should probably take a little bit of time to find a community that is right for you. On the other hand, you could start out by joining one of the “big” general servers, like mastodon.social, and then migrating to another instance later. Because moving between instances, and keeping your followers as you move, is something that’s entirely supported.

Alternatively, you can run your own server, and spin up your own Mastodon instance.

Why do you have your own instance?

We’ve opted to host our own instance. We’ve done this because, with multiple instances out there, we had to decide how to make sure people following us knew that our Raspberry Pi account was the “real” one.

Distributed systems are an interesting corner case when it comes to trust. Because when it comes to identity, you eventually have to trust someone. Whether that’s a corporation, like Twitter, or a government, or the person themselves. Trust is needed.

With Mastodon the root of trust for identity is the admin of the instance you’re on, and the admins on all the other instances, where you’re trusting them to remove “fake” accounts. Or, if you’re running your own instance, then it’s the domain name registrars. The details of our domain registration of the raspberrypi.social domain may be redacted for privacy, but our domain registrar knows who we are, and is the same registrar we use for all our other domains. They trust our government-issued identity to prove that we are Raspberry Pi Ltd. You can trust them, they trust the government, and ultimately the government trusts us because they can use Ultima Ratio Regum, the last argument of kings.

Although we are hosting our own instance, the development of the platform is all done by the folks at Mastodon. Mastodon itself, that’s the company behind the network, is a non-profit corporation based in Germany which is supported by both its sponsors and patreons, and because we’re committed to supporting platforms that support us, we’re putting our money where our mouth is and have become a platinum sponsor of Mastodon.

Are you leaving Twitter?

No. We’re not leaving Twitter: we like it there. It’s been our home these many years, but if the worst comes to the worst, we’re now part of the #TwitterMigration.

You’ll see us posting very similar stuff on both platforms, although Mastodon does offer us a bit more flexibility, including larger character counts and moderation that we own ourselves. So you’re going to see more content from us on Mastodon than you might on Twitter.

Because, right now, the way Mastodon presents posts is much more to our tastes: we have always preferred to see a feed made up of what the people we follow have to say when they say it. Twitter’s decision to curate the tweets in your feed never sat particularly well with us.

It is, however, vanishingly unlikely that you will ever hear any of us use the word “Toot” in conversation.

But I don’t know anyone?

You know us? But if you’re anything like us, you have probably spent a bunch of time trying to figure out who you want to follow on Twitter so that your timeline is full of kittens and puppies rather than Nazis and book burning. You’re not alone there, so people have gone off and built tools to help you migrate from Twitter into the fediverse. There are actually a bunch of tools, but the one we’ve used ourselves is called Debirdify. It uses some clever searches of people’s Twitter profiles to try and figure out if they’re also on Mastodon, and if so where.

Can I host my own instance?

Yes, but you’ll need your own server to do that. Our instance is running on a Raspberry Pi 4 hosted in a rack at Mythic Beasts in London, and it’s going to be rather interesting to see how it scales up.

You don’t have to host your instance on a Raspberry Pi, but if you can, why not? Right now both our instance, and Mythic Beasts‘ own instance, are hosted on Raspberry Pi 4.

Full details are coming later, probably sometime next week, when we’re going to do a full walk-through of how to host your own instance, including talking about how to do IPv6 natively with Mastodon. Because if your computer costs $35, your IP address shouldn’t have to cost $50.

If you want to host your own instance with Mythic Beasts, you can. Their host your own Raspberry Pi service is £7.65 per month, which comes awfully close to the new price point for Twitter Blue, and comes with 20GB of disk space. Alternatively, if you need to host a larger community, they’ve also committed to offering fully managed Mastodon instances. You can contact them for more information.

Either way, see you in the fediverse?

The post An escape pod was jettisoned during the fighting appeared first on Raspberry Pi.

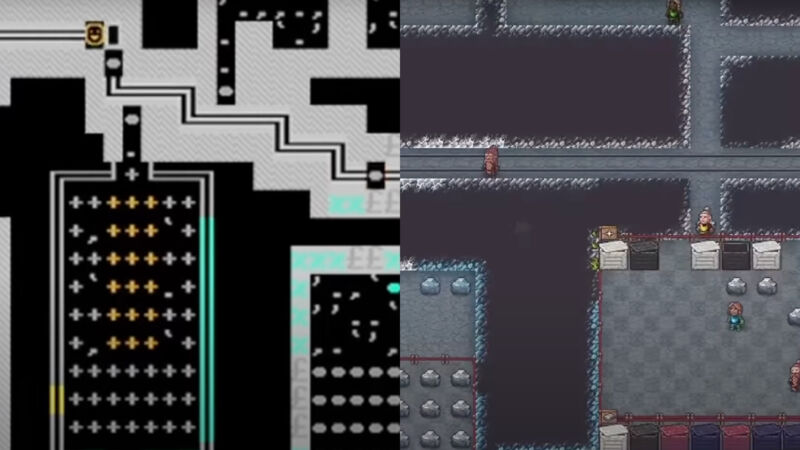

Enlarge / Two views of a Dwarf Fortress scene, in the original graphics and in the upcoming Steam/Itch.io release. (credit: Kitfox Games / Kevin Purdy)

The version of Dwarf Fortress that looks and sounds more like a game than a DOS-era driver glitch will be unearthed on December 6, the creators and its publisher announced Tuesday.

There's a trailer, a $30 price, and, should things go as planned, versions for Steam and Itch.io arriving that day. Buying these editions gets you a version with graphics, music, an improved UI and keyboard shortcuts, and—perhaps most importantly—a tutorial. It also supports the brothers who have worked on the game for more than 16 years, offering it for free and subsisting on donations. That free version of the game, ASCII graphics and all, will remain available.

You can see the difference in looks in the release trailer:

Dwarf Fortress Steam Edition trailer, featuring pixels that most humans can interpret as representations of real objects.

Or, for those not keen on moving-picture embeds, here are a couple of screenshots showing near-identical scenes from the trailer:

-

Here's a screenshot from the Dwarf Fortress release trailer with the ASCII graphics that fans have seen for 16 years... [credit: Kitfox Games / Kevin Purdy ]

While the trailer is focused on the Steam release, Dwarf Fortress will also be sold through Itch.io, where creators typically receive a greater portion of proceeds. That's important for Zach and Tarn Adams, the two creators and coders who have seen the project through, and both dealt with family health concerns in recent years, including a cancer scare for Zach in the late 2010s.

What's the game actually like? Former Ars writer Casey Johnston spent 10 hours searching for that answer. Here's a snippet from her report:

I’m already in this thing, eight or so hours deep, so it's time to solve a problem. Googling the "non-economic stone" error takes me to the wiki. This error can happen “when a dwarf walls himself into a corner and is unable to leave to get more rocks. Be careful where you build your Mason's workshop, as some parts of it obstruct movement.” Otherwise, there may just be too many kinds of economic rock around (stone reserved for a special purpose) or a stockpile might block the loose stones that might be used for making things. I should be able to mine more and generate more loose stones, but I try mining around. Not a single thing changes.

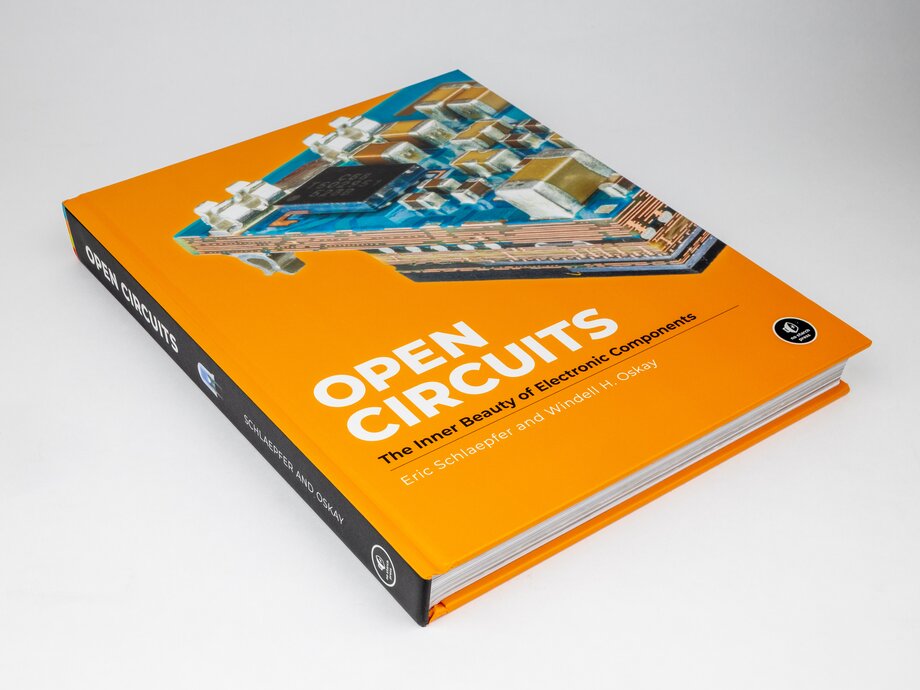

Earlier this year, I wrote about my then-forthcoming book, Open Circuits: The Inner Beauty of Electronic Components, co-written with our regular collaborator Eric Schlaepfer.

Open Circuits is a coffee table book full of close-up and cross-section photographs of everyday electronic components. And, it’s now shipping! As of today, it’s available in hardcover from your local bookstore, as well as to purchase online and in electronic versions.

We also just launched a new website for the book, with links of where you can purchase it as well as lengthy galleries of images from the book and of outake photos.

We put up a list of sellers on the website, including direct from No Starch and our own store, where signed copies are available.